- Markets

- Services

- Serial 1 Automation

- Aviation

- Coastal and Waterfront Engineering and Dredging

- Construction Services

- Engineering-Led Design-Build

- Engineering for Product Manufacturing

- Geospatial and Geophysical

- Distribution and Logistics Systems

- Mining Services

- Remediation

- Solid Waste Services

- Strategic Consulting and Planning

- Transportation

- Water and Wastewater

- Projects

- Insights

- About Us

- Join Us

- Contact Us

Why are we talking about PFAS?

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) have been a popular topic of conversation over the last number of years. PFAS may have the largest impact on water and water supplies of any group of chemicals ever developed. In recent months, since U.S. EPA has taken regulatory actions regarding PFAS, we have observed the emergence of broader discussions about how to move forward. There is a lot of complexity around this topic and no shortage of content but, given the significance of this issue, we offer our thoughts on the current state of the PFAS story to help you cut through the fog. Emerging contaminants of concern like PFAS require careful consideration and navigation in the current regulatory environment. Applying technology or presumptive solutions without a full understanding of your unique circumstances can lead to exacerbating your fiscal and environmental risk.

Until recently, there have been a lot of questions regarding what effect regulations might have and, given the patchwork of state regulations, how those might develop at the national level. Some of these questions have been answered with the U.S. EPA issuing federal maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for drinking water. For some organizations, this is good news because it is clear what requirements they must meet. While the federal regulations have made progress, state and local regulations are still not fully developed. Many questions remain.

How PFAS regulations will impact businesses is as varied as the industries we serve. The science and engineering communities have made significant progress in understanding the environmental nature and fate of PFAS contamination. Using what we have learned from our work addressing other chemicals in the environment over the last 40 years makes the paths to address PFAS clearer. But there is still complexity in the marketplace that poses challenges.

Below we briefly describe what PFAS are and why it matters to our customers. We then address a question that we are often asked which is “Can it be destroyed?” Within that context, we provide a general description of some of the technologies commonly discussed around addressing PFAS. We end this article with a summary of things to consider regarding the progress being made.

What are PFAS?

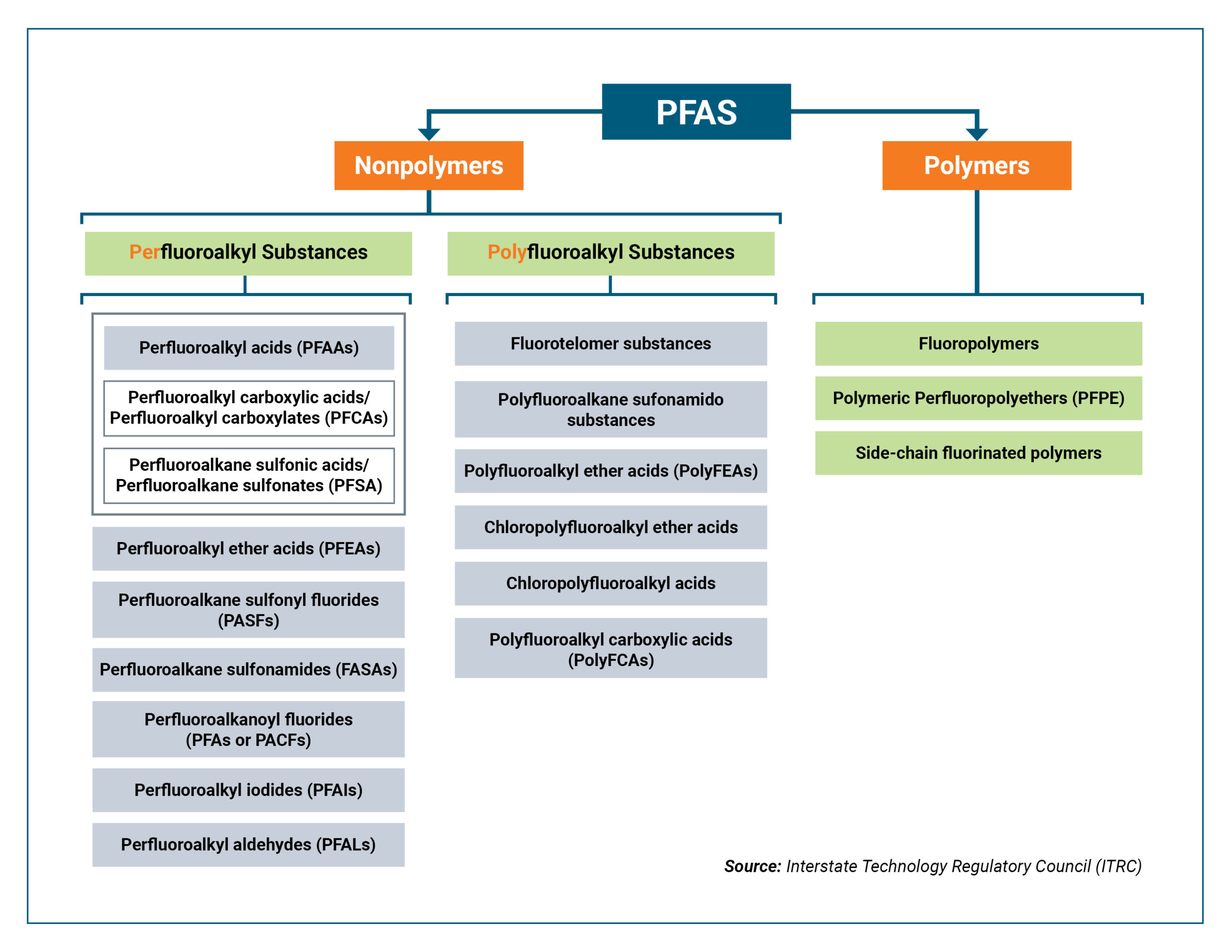

PFAS are a complex assemblage of roughly 15,000 different compounds that were developed since the 1940s. An interesting and detailed discussion of PFAS can be found on the U.S. EPA’s Contaminated Site Clean-Up Information website and at ITRC’s website. PFAS compounds are organic chemicals that are stable under a wide range of conditions and were found to be useful in products that need to withstand extreme temperatures (e.g. fire-fighting foams and coatings for cookware), extreme pressure, and require stable lubrication. The properties that make them useful also make them very durable. This durability has led some to call these “forever chemicals.”

Why does it matter that PFAS are in the environment?

PFAS compounds are to a greater or lesser degree toxic and pose a risk to human health and the environment. More detail regarding the toxicity of PFAS compounds can be found in the toxicology references on the U.S. EPA’s CLU-IN and ITRC’s websites. Chemical analytical laboratories worked for several years to develop methods to detect PFAS at the low concentrations that were necessary to properly evaluate their nature and extent. Having developed useful and repeatable analytical techniques, PFAS compounds have been found in virtually all environmental media, in humans, and animals. They have also been found geographically all over the world and in many products around us. That said, they are not found everywhere and, where they are found, they are not necessarily at concentrations that pose health concerns. Being as widespread as they are, science and engineering communities have been involved in the conversation of what to do about them and have been asked to develop solutions to the problems they present.

Can PFAS be destroyed?

Over the last few years, several methods of destroying PFAS have emerged. Some of these methods are adaptations of already existing treatment technologies, some are novel but proven to be effective, and some are emerging from their development stage. Challenges still exist such as scalability, energy requirements, production of byproducts, and relative cost but development is quickly progressing. Many of the destruction technologies are still in the experimental stages and will require further development to become full-scale and broadly applied. Several of the technologies rely upon high temperatures or highly controlled conditions and significant energy input. Byproducts are in some cases harmful and must be managed accordingly. Costs for many of the technologies, including ongoing operating costs, can be significant.

Examples of destructive technologies include:

- High-Temperature Incineration: High-temperature incineration is widely used for destroying PFAS. This technology processes PFAS-containing materials at temperatures exceeding 1,000°C which breaks down the carbon-fluorine bonds converting them to carbon dioxide, water, and hydrogen fluoride.

- Supercritical Water Oxidation: Supercritical Water Oxidation oxidizes PFAS in water at high temperatures and pressures. The breakdown products include carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic salts.

- Electrochemical Oxidation: The electrochemical oxidation process uses electric current to generate hydroxyl radicals that oxidize PFAS in either aqueous or non-aqueous form. Breakdown products include carbon dioxide and fluoride ions.

- Plasma (Ionized Gases) Technologies: Plasma technologies such as plasma arch apply a significant amount of energy to generate reactive species that can break down PFAS.

- Hydrothermal Alkaline Treatment: Hydrothermal Alkaline Treatment uses a strong alkaline solution at elevated temperatures and pressures to breakdown PFAS.

- Photocatalysis: Photocatalysis uses light-activated catalysts such as titanium dioxide to generate reactive species that break down PFAS in water and air. Using ultraviolet light, the breakdown products include carbon dioxide and fluoride ions.

- Sonolysis: Sonolysis uses ultrasonic waves to generate cavitation bubbles in a liquid during which the collapse of these bubbles produces extreme temperatures and pressures which breaks down PFAS.

An important challenge with most of the destruction technologies is that they can treat only a limited amount of PFAS in soil, water, air or other media at a given time. To address this, an obvious solution is to concentrate PFAS before it is treated to permit reasonable rates of destruction.

Concentrating PFAS: Technologies have been developed to concentrate PFAS in a media to reduce the volume of waste that needs to be disposed or destroyed. These concentration technologies, coupled with the destruction technologies, are useful in the search for practical solutions to destroy PFAS or, if not economical, reduce the volume of impacted media prior to disposal. Some examples include:

- Granular Activated Carbon: Granular activated carbon has been shown to be effective in the removal of PFAS by adsorbing the compounds onto the surfaces of the carbon. It is notable that although effective, the capacity of carbon to remove some smaller PFAS compounds is relatively low which results in those compounds “breaking through” relatively quickly.

- Ion Exchange Resins: Ion exchange resins have been demonstrated to be effective at capturing PFAS from water. The resins have electrically charged sites that fix onto PFAS molecules. Recent developments improve compound-specific adsorption.

- Nanofiltration and Reverse Osmosis: Nanofiltration and reverse osmosis use membranes that filter PFAS from water. This method works well for PFAS because of the generally large size of PFAS compounds.

Sequestration: Sequestration of PFAS is another technique that will have a significant impact on how we address contamination that cannot easily be destroyed. These technologies leverage the knowledge and experience the industry has gained on how to apply similar chemistry to address other chemicals. There are many circumstances in which removing PFAS and destroying it will simply be impractical and may be impossible. Sequestration has been demonstrated to be effective to a significant degree in those cases and poses what could be considered a reasonable risk. This may prove to be the best reasonable solution for many situations.

Materials for sequestering PFAS include:

- Granular Activated Carbon and Colloidal Activated Carbon: Granular activated carbon and colloidal activated carbon have been shown to be effective in the removal of PFAS and have been successfully injected into the subsurface to form barriers to further migration.

- Biochar: Biochar is a type of charcoal produced from organic materials that has a highly porous structure and high surface area, similar to granular activated carbon. Biochar has been demonstrated to be effective in sequestering PFAS from soil and groundwater.

- Clay Minerals: Clay minerals, such as montmorillonite and kaolinite, possess electrically charged surfaces which attract and sequester PFAS in soils.

- Other materials are under investigation including certain polymers and nanotechnologies to support sequestration of PFAS in environmental media.

Are We Making Progress?

The science and engineering communities have made significant progress in detecting and understanding PFAS, how they behave in the environment, and how we might destroy or immobilize them to reduce or eliminate the risk they pose. Evaluating the options and making financial investment in addressing PFAS is a difficult task but there is much more information available today than there was even a few years ago. Things to consider:

- Concentration of PFAS: High concentration PFAS, such as in soils near a fire training area, will require much different approaches than low concentration PFAS in water. The relative performance and efficiency of destruction, concentration, or immobilization will be different based on the concentrations present.

- Volume: Many of the technologies mentioned above have not been scaled to large or complex sites with large volumes of impacted media. When technologies are being compared for high volume sites, costs will increasingly become a determining factor in the applicability of certain technologies.

- Environmental Conditions: The conditions of the site will have a significant impact on the selection of the approach to address PFAS in the environment. The geology and hydrogeology of a given site, along with the concentrations in media, may have the most impact on selecting an approach to treatment.

- Taxonomy of PFAS: The realization of the sheer number of PFAS compounds prompted a convention to broadly categorize them based on the molecular structure. The molecular conventions include the carboxylate and sulfonate functional groups, the short- and long- carbon chain length groups, and the polymerized groups. Since PFAS releases into the environment will contain compounds from different groups, treatment technologies are being developed and evaluated to efficiently remove specific compounds. Co-contaminants present at the same time can complicate selection of effective solutions.

- State of the Available Technologies: Although many of the technologies mentioned here and elsewhere have been deployed, their long-term efficiency and effectiveness has not fully been determined, and the scalability has not been fully explored. Therefore, the overall environmental impact and sustainability of these approaches have not been determined.

- Stakeholders: The public perception or acceptance of the technologies has not yet been widely researched. Work is needed to build a broader understanding of the risks of PFAS in environmental media and the appropriateness of the scientific solutions identified here.

Spelling out PFAS and PFOS is difficult enough; understanding their properties, impact, and potential remedies can be a major challenge. If you have questions or would like to discuss PFAS or other environmental issues with our experts, please feel free to contact us.

Markets: Airports, Manufacturing and Industrial Products, Municipalities, Solid Waste, Utilities

Services: Engineering for Product Manufacturing, Environmental and Regulatory Services, Remediation, Solid Waste Services, Strategic Consulting and Planning, Water and Wastewater

Related Insights

©2026 Foth, All rights reserved.